Article 7: Healing Involves more than Drum Making: An Interview with Robert Lathlin

Nateshia Constant

Notes from the interviewer:

Some of the content shared by Robert Lathlin may trigger emotionally negative feelings to the reader. Robert Lathlin (Bob) is an intergenerational victim of the residential school system and a survivor of Indian Day School, Manitoba. Bob has experienced trauma, and he would like to share his experience of healing for himself. He hopes to encourage others to seek healing as well. Furthermore, he hopes that by talking about the hard times he experienced as both a victim and a survivor, he will be able to educate people on the subject of what really happened during colonial time in Canada. We (i.e., Bob and I), encourage the reader to take care of their spirit in ways that will be of any help to them, and they should reach out for support if needed.

Introduction to the interview:

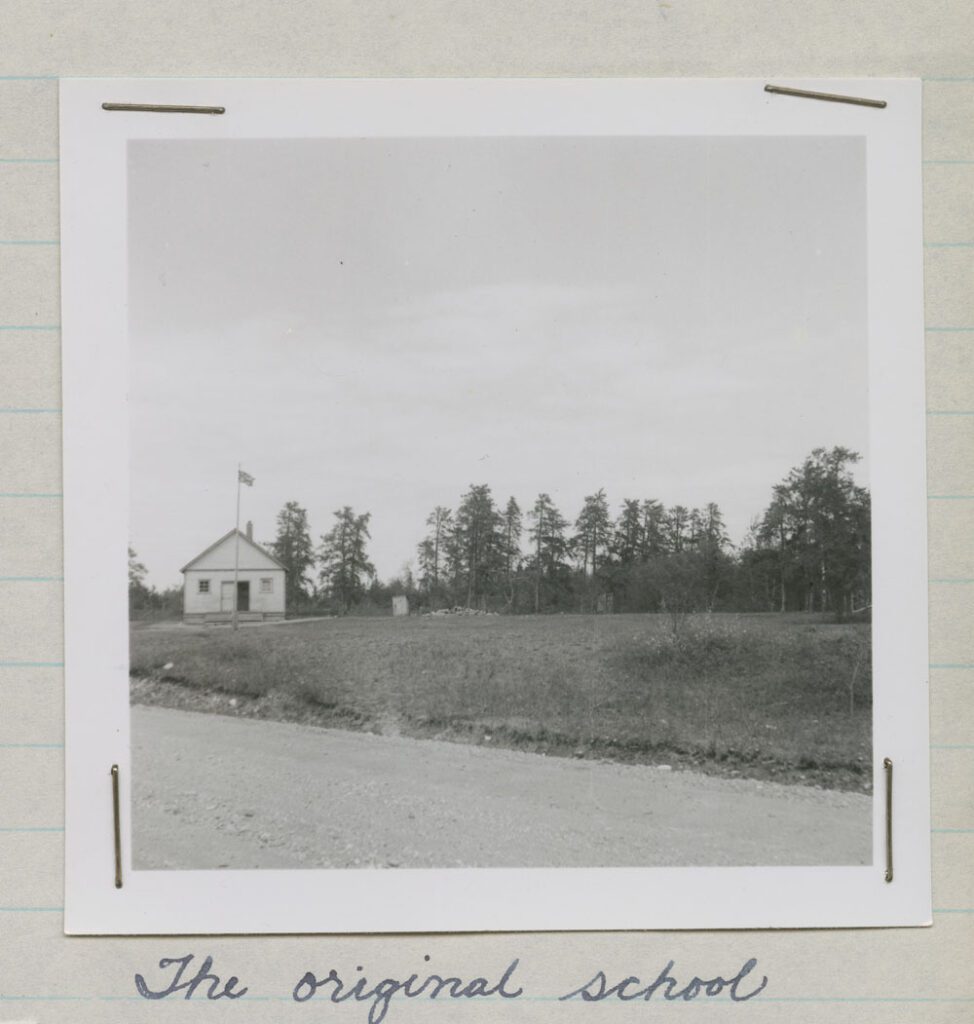

Robert Lathlin is a 59-year-old man who attended day school in Manitoba, Canada. He is a member of the Treaty 5 band from Opaskwayak Cree Nation. Robert Lathlin wants to share his story about being in day school in Manitoba. He attended school at Big Eddy Day School in Opaskwayak Cree Nation, and later Kelsey School in The Pas Manitoba. Even though Kelsey school was not an official day school, Robert mentioned that it was run exactly like a day school. He believed that his stories still need to be heard.

Robert Lathlin grew up in Cow Head on Opaskwayak. He grew up with five friends who were born in the same year as he. They were close-knit friends; they went to school and played soccer together. Bob grew up on a trap line where he learned how to hunt chickens by himself. At other times, he would go chicken and duck hunting with his parents and cousins. He spent almost half his life in the wilderness.

Bob talked about his experience growing up in day school which was a step down from Residential school. He started day school in Kindergarten at Big Eddy Day school in the year 1965-1966. Back then, Residential School and Day School were meant to mould the child into the colonizers’ standards; so, education, as we know it, was not on the main priority. First Nations people were ranked at the bottom of the scale when it came to social order. The colonist felt it was their prerogative right to “Beat the Indian out of the Child,” as expressed by Robert Lathlin.

Robert was not shy about sharing his experiences of what happened to him while he attended school. He, unfortunately, was a victim of the colonial way. After sharing his understanding of the concept, he also shared his abuse experience at day school. From his stories, we can feel the emotional, mental, traditional, and physical abuse he and his peers endured at the schools. The abuse started on Bob’s first day of school, when he was humiliated. That experience still haunts him today. On that first day, they were served stale rock-hard cookies that had been left out for days on end. According to Robert, taking a bite out of the cookies felt like biting a piece of rock; it was not even edible. “It was not nice,” he said. That first experience was an indication of future sad experiences to which they were subjected. He felt sad because back then he was a six-year-old student and he knew the school and teachers there would not care about them. The school became a place where the children could identify who was rich or poor. The children’s family background informed how they were treated by staff at the school. Most of the First Nation children were considered poor, and they were treated badly. Some of the teachers were just teacher assistants, but they were officially teaching even though they were not certified teachers. Since the school system was delegated to colonizing the First Nations, formal education was not on the top of their teaching priorities. Bob felt cheated by the day school education system. He felt as though he was a money-making pawn because people were only there to make money off the children. that the quality of education delivered at the schools were seriously lacking as evident by the fact that some students couldn’t even read or write in English. The classroom looked like a big area where there were no doors or walls, except for the romper room where students with special needs were separated from their peers.

At Kelsey School Division, there has never been a day school that is considered proper for Aboriginal children. When Bob moved to Kelsey School, he felt that the system at the day school was similar to what he was receiving at Kelsey School. So, Bob felt that there was a need for people to share day school stories in order to understand the situation of Aboriginal children. No matter whether it was day school or the Kelsey School that Bob attended, he felt as though the models of education were the same. Growing up, Robert was taught in a system which was considered inferior to others because he had special needs. While attending school, he never really learned to read and write because he was referred to as Aboriginal children retard. The hardest part of school was what they called the romper room, which was walled off for special needs students. Being sent to the romper room was not only difficult for students, but it was also easy for students to get into more trouble. The students could get into trouble for minimal infractions and they would be dragged out of the room by their teacher to the office to get strapped, or whipped. Bob told me that the children got hit on their hands until they were red or their skins broke, only then were they allowed to return to class. It was the hardest thing for Bob especially when he was called names such as “retarded and idiot.” Bob felt that all through the years of being put thorough special education, he and his peers really didn’t get any education as they just passed through the system. “The adults who were suppose to look after us seemed to not even care. So, in return, we did not learn to read or write properly. We were deprived of the education which was ours by right.

It was difficult for Robert to remember his days in day school. When I asked Robert if he wanted to share a specific experience which he had during those days, he told me that it was not just a one-time experience; rather, it was a daily affair at the schools. However, he managed to mention three specific cases to highlight how badly he was treated during his years at the schools. According to Bob, “when I got to Grade 5, the gym teacher manhandled me. He treated me like shit.” Bob said he felt as though the gym teacher was nine feet tall, compared to his little body of only four feet. The teacher took him into the washroom to wash the floor with just a tooth brush. He continued, “We had to cover every inch of the floor; the teachers would stand there and call us dirty Indians just because of the color of our skin.”

Bob also recalled that in Grade 7, he was maltreated by another gym teacher because he had talked with a Caucasian girl. Children of First Nations were forbidden to talk to people other than children of their own ethnicity. After talking with the Caucasian girl, the gym teacher punched and knocked Bob out. While he was unconscious, he was dragged to the office. Luckily, nothing worse happened. When he came to, he was sent right back to class. The last memory he had of his later days in Day School was the punishment he took for not returning to school on time. The principle had him up against the wall while holding his neck in a choke-hold and calling him derogatory names. The principal yelled into Bob’s face: “Don’t come back to school any more!”

When I asked Bob if he had any fun memories of attending day school, he started off first by saying he thought the teachers were there just to collect their money. Bob felt they weren’t there to teach children but to pass their time leisurely for money because the teachers had no formal education themselves. Therefore, Indigenous children did not receive proper education. In terms of learning in day school, Bob only has a few odd memories. He remembered that a teacher named Mrs. Cloud helped them to spell their names, and taught them their social insurance number because she said that was something they would need to learn for their future if they wanted to survive in the society.

Nateshia Constant: What was a typical day in day school?

Robert Lathlin: A typical day usually had physical altercations. It was so bad that some students paid other students to protect them from being bullied. The teachers didn’t care who would be bullied and they would turn a blind eye, or they would punish you even if you got bullied. Typically, it was very rough for the students as they went out to play, they could not just enjoy being a child playing on the playground because they had to protect themselves. A lot of the altercations came from being poor or being a child of the First Nations. I had a strong feeling that the teaching staff did not care for us no matter what we, my sister and I, had been through. While my sister was in Grade 7, she got one of her ears ripped off in class by a teacher. School life was very tough for us because we were considered as Indian children. I just wanted to feel protected by the school system but it failed me completely. I also feel let down by my parents who couldn’t do anything to protect us and I was mad they did not know I needed protecting because they attended Residential School.

Note: Bob’s parents thought that the way of the day school was correct because that’s what they were taught as right. He felt disappointed because of the lack of help from our band because they let students go through this kind of schooling.

Nateshia Constant: Did the Residential School system affect your family?

Robert Lathlin: It affected us a lot. When I was growing up, my dad brought the abuse home from Fisher Island Residential School. I watched him wake up crying from his memories. He brought home with him the terrible memories of being abused. He was always angry that he sought relief in alcohol. We are still going through this cycle. After I became a dad, I stopped drinking because of what I saw my dad go through. I did not want to repeat my dad’s problems. I wanted to break this bad cycle.

Nateshia Constant: What are the ways you learned to cope with the effects of Residential School stemming from your father’s attitude towards you? Do you still need to use the same mechanisms today?

Robert Lathlin: Well, that’s the things I don’t understand. Actually, there is no mechanisms involved. I had to learn how to cope with anger as a result of the things I went through with my father. He had to learn a lesson by learning from his own and others’ mistakes. By realising the mistakes they made because of the things they suffered, I should try to change myself for the better. I tried my best to break the cycle. I tried to push all my kids to graduate from either high school or university. Because of my own experience of learning nothing at day school, I didn’t want them to grow up like me. I wanted my children to have a happier life and to be the best part of themselves. I did not want my kids to share the same struggles as I have had.

Nateshia Constant: I appreciate your sharing your thoughts and feelings about both the residential and day school with me and my readers. It is painful to remember those days but you have done it. What’s your motivation?

Robert Lathlin: My last thoughts were that the truth has to be told. Truth and reciliation has to be done within one’s self before sharing with others. I believe that leaning towards healing should not only be by making something, for example like a drum. I think one can’t heal by only making a drum. I feel there must be more needs to be met than making something. Only making some object is not healing at all. There should be more professional helpers made available to victims at all levels. I would like to have more help from my band. I think that people shouldn’t only heal together with the community, but also, they need time to heal alone first and to be good within themselves before everything else. I think there are so many people still suffering from their terrible memories and traumatization from day school and residential school. One could just look in the streets and see all these hurt people who don’t know how to help themselves because they were not taught how to recover from hurting. We are still learning to accept the past and it takes time and one should allow us to heal in our own ways.

Note: For himself, Robert realized that he needed to quit drinking because no one but himself could really help him through the hurt. According to him, quitting drinking taught him how to stop the anger: “Nobody understood how I suffered except for myself. Thus, I helped myself. I quit drinking, and I constantly reminded myself that the past would still come back to me if I don’t control myself.” Bob said he has learned how to work with himself by saying, “I’m not a broke Indian but I’m an Indian full of love and care for other people. Through my own experience, I feel that people should be okay with themselves before they share their feelings with the world. People need to learn to be okay in order to share and heal from memories and emotions. I want to see more people being able to have one-on-one conversation with professionals who could help them to heal.”

Nateshia Constant: Is there anything you want to add?

Robert Lathlin: I’d like to see a better system to help with the healing process. Healing focuses on people and the system should take people seriously not only by trying to ask them to do native crafts. We need people who will really help us; we need professionals who can help us to recover and heal from hurt and trauma. I want to sit in a circle with people who have deep wounds and invisible hurt, and who would change by listening to other people’s stories. I want to see Chief and Council push for the people from the residential school and day school to do something about themselves. I really want to see us, the victims, get help more than we lost. For the people who lost their children to residential schools, they should still get monetary compensation from the government. So, I think the band should get the circle going, and they should speak out for those families. I always hear people say that the wheels stop rolling, but it’s not we who need to keep it rolling. It is also a fact that people with disabilities due to the intergenerational trauma need more help. I can say that I did it myself, and it proved to be hard. My experience told me that people who can’t talk about their sufferings need more help to get healed. Therefore, their needs should be prioritized in the healing process. The key issue is we need to look way back to hold people accountable. Everyone is equal in today’s world and there are no higher or lower rankings of human beings. I want to share my stories so that everyone will learn to hold themselves accountable in all that they do.