Article 4: A Portfolio of the North: The Conflicting North

Shaila Moodie

Northern Canada was created around 1867-1870. Since then, there have been various conflicts, mostly between races. The overriding theme of this portfolio is the clashes between the Aboriginal society and non-aboriginal peoples. I have put together twelve items in this article that showcase “The Conflicting North”. I will use examples from as early as the 1800s to as late as 2017 to show the various conflicts between peoples or cultures in the geographical area known as Northern Canada. Illustrated events in this portfolio provide an analysis of the conflicts and the impact of the conflicts on mainly the First Nations people.

Dickason, Olive, et al. “Mistahimaskwa & Pitikwahanapiwiyin in Detention (1885).” Indigenous Peoples within Canada; A Concise History. Oxford University Press, November 2022.

Mistahimaskwa and Pitikwahanapiwiyin are two of the most famous Plains Cree Chiefs. Their names translate from Cree to English as ‘Big Bear’ and ‘Poundmaker’. They had much influence in the resistance against signing Treaties Six and Seven. The photo was taken while both chiefs were in federal detention (1885). Mistahimaskwa was forced to cut his hair to be humiliated and to be stripped of his Indigenous identity. Long hair in Aboriginal cultures is considered to be sacred. Pitikwahanapiwiyin, on the other hand, was allowed to keep his long hair due to the intervention of his adoptive father. Poundmaker’s father was known as Crowfoot, he was a negotiator for Treaty 7 territory.

The incarceration of the two famous Indigenous men took place following their refusal to sign Treaties Six and Seven. Mistahimaskwa, in particular, did not agree with what was proposed by the Canadian government after long negotiations. Hence, the government’s response to his refusal to sign Treaty Six was the taking away of food rations meant for his community. He refused to sign Treaty Six in particular because it was equivalent to signing away the indigenous law of the land; in return, the Queen offered the First Nations gifts such as tea and tobacco. Mistahimaskwa’s response to the Queen’s overture was, “We want none of the Queen’s presents. When we set a trap for a fox, we scatter meat all around, but when the fox gets into the trap, we knock him on the head. We want no baits. Let your Chiefs come to us like men and talk to us” (Dickason et al. 214). However, at the end of all the back-and-forth “negotiations,” Mistahimaskwa was forced to sign Treaty Six in the year 1882 due to the apparent genocide against his people.

In 1885, the first proposal of “The Metis Declaration of Rights” (also known as the 10-point Bill of Rights) produced by Louis Riel was introduced, which led to a rebellion initiated by the Metis. Both Mistahimaskwa and Pitikwahanapiwinyin, along with other chiefs, participated in the rebellion. In May and July of the same year, the two Cree Chiefs surrendered and were imprisoned. However, they were released before their three-year sentence was up. Shortly afterwards, both men died due to health conditions.

David Collins & Tom Creighton Confliction of 1914. Oral Story retold by David Moodie. November 18th, 2022.

There are many versions of the David Collins and Tom Creighton Conflict of 1914, however, the following story is what my grandfather, David Moodie, has told me. He was familiar with the conflict because David Collins was a big part of his family ancestry; he was also my great-great-great grandfather. David Collins was a First Nations member. He owned a trapline where he discovered a massive volcanogenic sulphide deposit on his land. Collins then showed Creighton his discovery. Because Collins was First Nations, he did not understand the importance of land ownership and how to claim this discovery. Therefore, Creighton took the new discovery to the right people to stake a claim to the land as their own. For many years, only Creighton was acknowledged as the founder of the Flin Flon mines.

Even now, the Flin Flon mines are still known to have been founded by Tom Creighton and David Collins. To my family, this is not truthful. The way it has been seen by our family is, once again, another story of a white man overstepping and claiming land that is not his and then making the Aboriginal man depend on him for recognition. In Canada’s history, this is one example of the most significant conflicts that have been happening in different ways between the First Nations and the Settlers. The Settlers believe that they are better than or have a higher hierarchy over the First Nations people.

“The Death of Helen Betty Osborne, 1971.” The Aboriginal Justice Implementation Commission.http://www.ajic.mb.ca/volumell/chapter1.html. Accessed 10 Nov. 2022

One of the most controversial and conflicting aspects of the North that Canadians still converse about is the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Movement. Although the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women has been around for over 40 years, the National Inquiry did not officially commence until 2016. Three years later, in June of 2019, the National Inquiry ended with no conclusion. Now is the time to react to this inquiry. This movement responds to the issues that Indigenous people, primarily women, deal with regarding the justice system. Systemic racism is the root of the majority of the First Nations’ problems. For instance, if a non-Indigenous woman goes missing, the authorities will send out amber alerts almost immediately. In contrast, when an Indigenous woman goes missing, the media would analyze the missing reasons such as “She is probably a binge or drunker. You will find her cracking cocaine or drinking somewhere”. There is one case I would like to mention because it hits close to home, The Pas, Manitoba, where I was born and raised. The victim’s story is one of the most widely talked about in the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Movement. In November of 1971, Helen Betty Osborne was abducted and fatally beaten by four Caucasian men in a cabin at Clearwater Lake, just outside of The Pas. Her remains were found the next day by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. However, it took a long time to find the culprits because the police assumed it was someone close to Osborne who murdered her. It was not until an anonymous letter was sent to the police stating who committed the crime that the prosecution started. The letter identified the men, Lee Colgan, Dwayne Johnston, James Houghton, and Norman Manager, all participating in the crime. Only Dwayne Johnston was charged and imprisoned. The prosecution happened sixteen years after Helen Betty Osborne was murdered.

Helen Betty Osborne’s story is one of the many cases of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women/Girls movement. “Aboriginal women face life-threatening, gender-based violence, and disproportionately experience violent crimes because of hatred and racism” (Native Women’s Association of Canada 3). This is the current conflict that affects the majority of the Aboriginal population.

Mosionier, Beatrice, et al. In Search of April Raintree. Portage & Main Press, 1983.

In Search of April Raintree is about two sisters in and out of foster care, growing up surrounded by death, abandonment, cultural genocide, and emotional, sexual, physical, drug and alcohol abuse. This novel has two main protagonists, April and Cheryl. They grew up in Norway House, Manitoba, and moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, due to their father’s health issues. While reading this book, I analyzed the struggles of Indigenous and Metis People, specifically the racism and discrimination towards them, using derogatory language such as “the savages” and “half-breeds.”

I observed that this novel defined the aspects of conflict in northern communities. It gives an excellent depiction of the foster system and points out personal views of how Indigenous children are treated differently in foster homes or group homes. Not only is the foster care system a concerning issue to various communities, but what is very concerning is the health care and lack of medical professionals, not only in the North but throughout Canada. Due to the inefficiency of the health care system, most northern communities must travel to Winnipeg or other cities to get proper medical treatment.

One colossal struggle is drug and alcohol abuse. Drugs and alcohol are a big struggle due to intergenerational trauma caused by the residential school era and the Sixties Scoop, significantly impacting Indigenous communities. Trauma passed down from multiple generations has significantly increased addictions and homelessness. In northern Canada, minimal resources and proper treatment facilities may lead to incarceration or homelessness. This crisis has pulled many families apart and ripped kids from their parents, placing them in foster care.

With many negative stories which the book brings to light, it also sheds light on the significant strides which Indigenous people have made, despite the challenging and traumatic childhood they were raised in. I am reflecting on the personal life of my grandparents, who attended residential school, and the lives of children of the sixties scoop. My family has struggled with alcohol and drug abuse caused by these past generational traumatic events that took place in the past decades. I am thankful for my mother and my father, who taught me hard work and dedication, thereby breaking the line of intergenerational trauma.

Harrison, Ted. A Northern Alphabet. Tundra Books, 2009.

Ted Harrison is one of the most famous Canadian artists. He was born in England, but after traveling to a few countries to teach, he finally decided to settle in Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada. Harrison quickly became recognized for his contribution to Canada’s culture only seventeen years after he settled in Canada. I say only seventeen because it has taken longer for the First Nations people to be recognized for their culture. Harrison was known mostly for his work with Robert Service in the poem “The Cremation of Sam McGee.”

His style of art is simple yet very colorful and eye-catching. His process of painting is also known as Serigraphy which is a type of art that is layered, mostly with ink. As I have mentioned, Harrison illustrated many books, including his own books, such as A Northern Alphabet. This book is a children’s educational story that uses various items from Canada’s northern territory, Yukon. This book is used to teach the younger generations the alphabet using examples such as “O- The Owl can see the Oil rig from the Outhouse” (Harrison 15).

I chose this as an example for the conflicting north portfolio as it is, once again, a British man colonizing the North. I say this because the North can be alphabetically sorted by all kinds of northern Indigenous items. However, Harrison makes his own twist by adding some colonization to a story that is clearly in an area that is surrounded by Indigenous peoples/objects. For instance, in most of the pictures illustrated for each letter, there is a symbol of settlers’ presence amongst these indigenous lands (airplane, Canadian flag, electricity poles, etc.). This stood out to me because Indigenous people hardly get recognized in the media, but when they do, there has to be colonized presence shadowing the acknowledgment of the First Nations’ culture. This is presented heavily in Harrison’s art.

Coles, Gregory. No Turning Back, National Film Board of Canada, 1996, https://www.nfb.ca/film/no_turning_back/. Accessed 17 Nov. 2022.

This film documents the two-and-a-half-year journey of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Communities. The Royal Commission Members travel from coast to coast, bringing light to the First Nations’ concerns and suggestions. The Government made this Commission seven months after the Oka Standoff in 1990.

The Oka Standoff was a conflict between the Quebec town, Oka, and the Mohawk peoples. Oka’s town assumed they could build a golf course on the Mohawks’ ancestral burial grounds. The Mohawk stood up for what they believed was right, preventing the golf course from building on these sacred grounds. The Canadian military and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police force met their resistance.

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal People contained seven members; of those seven, more than half were of Aboriginal descent. They traveled to over one hundred communities and interviewed over one thousand First Nations peoples. Many interviewed people were passionate about what they had to say and did not hold back. Some were hesitant because the Government created the commission, so they did not believe anything would be done about what they had to say. However, three main points stood out to me throughout the entire documentary: What were some of the critical conflicts that led to the Oka Standoff? What kind of issues were raised after the disputes? Finally, what can the Government of Canada do to prevent a reoccurrence of the Oka Standoff or something similar?

Many conflicts have happened between the First Nations and the Government of Canada. The first cause of the Oka Standoff was the lack of acknowledgment of the sacredness of the Mohawks’ ancestral burial grounds. Now, Aboriginal people do not believe in ‘owning’ land. Instead, everyone should treasure and take care of the land. This can be very conflicting because, from the first contact, colonizers could not grasp this concept. However, it does not take much to understand that a burial ground can hold a lot of sacredness to a tribe or a person. The Government and the Frist Nations people do not understand one another’s culture. Another conflict is the Government treating First Nations as people who need to rely on them (i.e., the colonizers) to show them the proper way of doing things. This is also known as conflicts such as Indian Residential Schools and the Sixties Scoop. These are ways of assimilating the indigenous population to the “white”. This was the goal of the Canadian Government for so long to take the First Nations culture away so as to absorb them into the mainstream culture.

Due to these conflicts, the First Nations people now have many issues to deal with in their communities. For example, after all the trauma during Residential Schools and the Sixties Scoop, people could not bear to live sober. Many Aboriginal people suffer from alcohol and drug addictions. If they had children, this led to their not knowing how to be good parents to their offspring because they never learned how to be themselves. This situation created the inter-generational trauma that most First Nations people have dealt with for several decades.

The documentary’s main point was to find a solution to prevent clashes between two cultures from happening again. Some of the solutions from the documentary were as follows: First Nations people need to stop accommodating others; for a change, let the other people adapt to the First Nation’s culture and traditions. The importance of acknowledging that First Nations people, as the Government would say, “own” this land; they have been here much longer than any other race or ethnicity. The Government needs to create safe spaces for the seven generations of Aboriginal people to heal, including traditional healing practices. Justice is necessary as a way for some people to start the healing process. The Federal Government needs to implement the First Nations’ traditional forms of justice so that we are not experiencing discrimination in the Canadian justice system. Finally, Canada needs to let go of the past and mend what is left of any relationship that the Government and Indigenous people have broken in the past.

All these suggestions were great; however, over thirty years later, we have not yet seen half of the recommendations implemented in Canadian society. This conflict between the Government of Canada and the First Nations people led to a lot of people finally being able to speak their minds freely. It was a step in the right direction to create the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People. However, the Government still has a long way to go to implement the final stages of healing.

Walter Cook (Great-Grandpa’s) Conservation Caves. 2001. Oral teaching by Norma Moodie told on November 9th, 2022.

The story was told by Norma Moodie who is my grandmother and the daughter of Walter Cook, an avid conservationist who discovered a cave in northern Manitoba. The Caves are now named after him.

There are many aspects to this ecological reserve that make it so unique and rare, and people come to do research on it. Not only are there bats wintering in them, but there are also rare flowers that bloom in the spring, such as the calypso orchid. Moths have also been found to be wintering in these caves. This reserve spans approximately 2,250 hectares, which includes six caves altogether. The Walter Cook Cave has a fascinating view of scallops forming on the roof. With help from the Government and the Grand Rapids community, they were able to make it a Manitoba Park. This means it is an area that is supposed to be protected and maintained, free from industrial work or any activities that can harm the environment. Therefore, the general public will need permission to obtain a pass which grants them access to the area. Luckily, First Nations people can explore these caves without requiring an access pass due to treaty rights and also as a form of reconciliation.

Walter Cook was born on December 3, 1917, in Grand Rapids, also known as Misipawistik Cree Nation. He spent his life hunting, fishing, and trapping to provide for his family of thirteen children and his wife, Nora. Living off the land, he only took what he needed; he was very conservative towards the natural habitats. When he discovered the caves, he did not let anyone know for years, not even his family. He wanted so badly to preserve this rare find that he would not tell his own family. Unfortunately, he would have to let the authorities know about this discovery due to finding bones which he thought were human remains, they turned out to be bear remains. Great-Grandpa Cook passed on the knowledge to protect and respect the land and what it offers to his children and grandchildren. In 2008, environmental destruction began. A fire broke out on the reservation, wiping out over one hundred thousand acres of land, including Great-Grandpa Cooks’ cabin. The fire started when a group of university students were conducting research in the area. They set fire to their wastepaper because they did not have the means to carry any extra weight with them as they already had so much equipment. The Government offered the Cook family $10,000 for the loss of the cabin. However, that cabin held great memories and many of Walter’s belongings, things that were invaluable.

This is the conflict that Indigenous people have been facing for many years—the encroachment and invasiveness of the Government when it comes to land. Many Aboriginal people still believe that land does not belong to anyone. Those who do not believe this have no choice but to accommodate the Government.

Obomsawin, Raymond. Traditional Medicine for Canada’s First Peoples. 2007.

Canada’s Aboriginal people who reside in this country’s boreal forest have used medicinal plants forever. Over time they have learned to use plants successfully and have maintained this knowledge through oral traditions. The settlers of this land have nearly obliterated this precious knowledge by banning healing methods. Many medicinal plants have been used to treat diseases and disorders. From many readings, I see that the settlers of this land have mostly stomach disorders and musculoskeletal issues.

The Aboriginal people’s knowledge of medicinal plants has not been appreciated until recently. Canada has yet to make policies to protect this knowledge and conserve, and harvest, so as to use medicinal plants as a priority. A review of Obomsawin’s book claims that it is the first to show the richness of the Aboriginal people’s knowledge. More research is required to conserve the medicinal plants in the boreal forest. Medicinal plants are still used as a health care source by 70 – 80% of people on this earth. The medicinal plants are also used as income for many people as well. Presently there are concerns that the valuable knowledge of medicinal plants is disappearing as fewer people are learning orally about these practices.

Aboriginal healing is strongly connected to spirituality and being in touch with nature. It also includes the closeness of the community and how they knew someone who is a healer, and people were sent to these healers according to their problems. Canada has a boreal forest that covers most of its land mass. In 2006, the census showed that there were 1,172,790 Aboriginal people in Canada, which amounted to four percent of its population. These forests have sustained the people physically, culturally, spiritually, and naturally.

Before settlers arrived in Canada, the healers were highly regarded. They were able to maintain the wellness of their people with plants and therapeutic methods. The arrival of Europeans discouraged traditional healing practices, and some were deemed illegal. Therefore, many of these practices were abandoned, and native people became more dependent on Western medicine and healing systems. Until recently, the value of the aboriginal people’s knowledge of their medicines has been realized. There is a push for the political author to try to preserve and regain these valuable practices. These practices are part of the Aboriginal culture, and they must be acknowledged. It is necessary to have the awareness that using medicinal plants is part of the Aboriginal culture and those practices can’t be stolen from Aboriginal traditional medicine.

Deerchild, Rosanna. This Is a Small Northern Town. J. Gordon Shillingford Publishing, 2008.

Rosanna Deerchild is a Cree poet from South Indian Lake also known as O-pipon-na-piwin Cree Nation. This book is the first collection of her poetry. In terms of defining a conflicting northern aspect, one that stood out to me was her poem titled “Paper Indians” (Deerchild 14). This research portfolio examines conflicts in the poem as Deerchild is forced to move out of her hometown, South Indian Lake, to the small city of Thompson. Many of Deerchild’s poems highlight some of the problems that Northern First Nations peoples have endured. Many have suffered from traumas with Indian Residential Schools and the Sixties Scoop. The issues include alcoholism, abuse, neglect, etc. Not long after, her mother meets a southern hunter and starts having a romantic relationship with him.

I chose this poem because I relate closely to it as I have felt the same as she does after a big move, out of place, and in a new and scary environment. I understand this feeling because I have moved to at least six different towns in my lifetime. A lot of them had people who exhibited racism in different ways toward me.

Looking at the first stanza, Deerchild uses a lot of adjectives to describe these “Paper Indians,” such as ‘draws, traces, cuts, and folds’. Deerchild describes how First Nations people can be easily controlled or assimilated to accommodate other people’s needs. In the second stanza, she continues with the adjectives describing her family as paper “pastes” (Deerchild 14). I would also like to point out how the descriptive language in the poem went from “dirt roads and rez houses” to “cement lines [and] box houses”. She acknowledges the differences between her hometown and the new, unfamiliar town.

One issue that may arise when moving to a new town is that the one moving may end up being around more strangers than friends. The strangers, in the eyes of the one moving, might already have their groups, and the moving one may feel frightened of what the people think of them. For example, the fifth stanza says,

at church dinners, he jokes

he went up north to hunt

a moose and he got five

laughter tinkles

like cutlery on glass. (Deerchild 14)

This brings to light what her stepfather thought of her family. He saw them as a prize to be shown to his fellow churchgoers, but not in a proud way. More jokingly, he is insincere towards them like they are just animals to him. The laughter which accompanies the joke, to Deerchild, in this new environment is like alarm sounds going off right in her ears. This is because she is most likely worried about what other people think of her and her family, and all they do is laugh at their name, their family name, Moose.

As I reflect on my own experience of moving to different towns in my life, I discovered how challenging it was for the speaker to go to a new place. I would feel anxious about entering a new school, making new friends, and meeting not-so-nice people. There were also those who needed help understanding where I came from. The ones who would joke about residential school, the ones who would speak a different language to me, then judge me for not understanding—that feeling of not belonging anywhere, not having a town to call home. I feel sympathetic for Deerchild in this poem as it emphasizes the unfortunate reality of moving to a new town and meeting unfamiliar people.

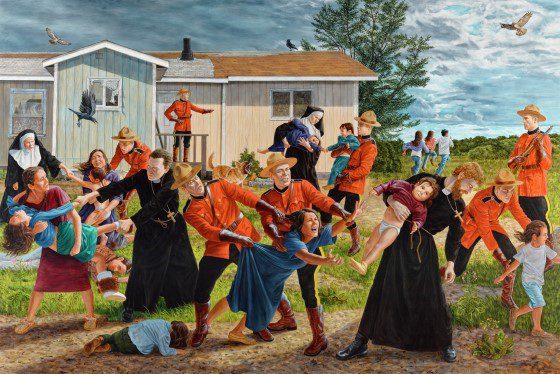

Monkman, Kent. The Scream. Oxford University Press Reproduced with Permission of Artist, Canada, 2017. aci-iac.ca/art-books/kent-monkman/key-works/the-scream/. Accessed 11 Nov. 2022

This painting captures the true tragedy and horror of the reality of what Indian Residential Schools and the Six Scoop honestly looked like in the eyes of the First Nations. Kent Monkman is one of the most famous Indigenous Canadian painting artists of the 21st century. He is known to paint history that includes Aboriginal presence. In this painting, he captures the tragedy, sorrow, and trauma that First Nations people went through as they were forced to send their children to Indian Residential Schools. This painting is very moving as he captures a mother’s unfortunate pain when having her child ripped away from her arms. Obviously, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the nuns, and the priests all show a lack of empathy and compassion for children taken away from their parents.

Paintings like this give non-indigenous people a perspective on what First Nations people have been through and why they suffer so much from drug/alcohol addictions. Many indigenous people have gone through this trauma. Most of them did not learn how to love because they lacked that connection with their biological parents, stemming from the acts of genocide perpetuated against their people. This lack of connection resulted in intergenerational trauma. Many families still suffer from this today. Intergenerational trauma can include signs of addiction, loss of culture and language, and physical, emotional, and mental abuse.

Intergenerational trauma is something that even my family suffers from; therefore, this image impacts me significantly. It represents the painful experience that First Nations people still deal with daily. The Government is working to fix these issues that Indigenous people have endured with the Truth and Reconciliation Act coming into being for more than ten years. I hope that one day, First Nations people will fully get healed, and the Government will work hard to prevent this painful episode in Canada’s history from happening again. However, Monkman’s painting will always be a part of our tragic history. This painting gives First Nations people a voice louder than words.

Author’s Bio:

Hello, Tansi, my name is Shaila Moodie. I am 21 years old. When people ask where I’m from, I like to say I’m from everywhere. I was born in The Pas. My band is O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation. My dad is from Misipawistik Cree Nation, which is where my mom lives. I call Cranberry Portage ‘Home’ because that is where my Grandparents live. I have moved all over the province. But for now, I am living in The Pas to attend University College of the North for my Bachelor of Arts and Education Degree. I have always wanted to be a teacher for as long as I can remember. I broke the cycle of drug and alcohol abuse in my family. June 8th, 2020 was the last time I had alcohol. Since then, I have had a baby named Cassius, he is now two years old. I was able to get out of debt and live in a nice house. I like to travel; I have been to five different countries and plan on going to more. I am Cree however I do not speak it as often as I would like, which is something I will work on for my baby. I am honored to have my portfolio published by this special issue of Muses from the North. One quote I like to follow is “you are the writer of your own story.” In this portfolio, I have written two stories: one is about the David Collins & Tom Creighton Conflict of 1914, and it is based on the oral story my grandfather David Moodie told me; and the other is about the disappearance of Water Cook Conservation Caves in 2001, and that is from the oral teaching my Grandmother Norma Moodie offered to me. There might be other versions of those two stories, but I am the writer of my own stories which tell the truths from an Indigenous perspective. The rest of the entries in my portfolio are my understanding and interpretation of “The Conflicting North” when I took the course Northern Image with Dr. Keith Hyde