Article 1 – Elder and Student Engagement with Knowledge Keeper William Dumas from South Indian Lake

by Alicia Stensgard

Interviewee: William Dumas

Interviewer: Alicia Stensgard

Date of Interview: September 16th, 2019

Location of Interview: Thompson, MB

List of Acronyms: WD= William Dumas, IN= Interviewer

Translator/Spell-Checker: Ron Cook and Maggie Moodie

IN: My name is Alicia Stensgard. Today I will be interviewing Knowledge Keeper William Dumas from South Indian Lake. If you’d like to introduce yourself William, that would be great.

WD: Tansi, nitotemak William Dumas nitisithikason. opipon-napiwinihk ochi. [Hello my friends, my name is William Dumas. From O-Pipon Na Piwin Cree Nation]

IN: All righty, so I’ll just start on the first question. So, I just recently got a copy of Pĭsim finds her Miskanow, which is an amazing book. I really enjoyed it. And honestly, the knowledge level pieces make this book (ahh) just awesome. I also checked out the app, which is really interesting, and I think, would be [pause] a great resource tool for education. [pause] So, I really enjoyed your story, like about Pĭsim finding her [pause] her way, her life journey. [Umm] Regarding your story about Pĭsim, who originally passed the story on to you- Or was it given to you in a dream?

WD: I grew up in (ahh) South Indian Lake, and- this was back in the day where there was no television. There were hardly any books to read. It was a very isolated community, very isolated! I remember listening to the stories of the elders around the kerosene lamp. Us sitting around listening to the elders. [deep breath] The first language that they spoke was Cree. So, all the stories were done in Cree. Soo (ahh) kids like myself, we probably didn’t speak English until we were about 8 years old. So, I grew up listening to storytellers and (ahh) listening to the storytellers connected me to the past. Because one of the things that the elders use to talk to us about was understanding the language, thinking in the language. That was our classroom, our first classroom. And because we were raised like that, it connected us to be proud of being Indigenous. While the rest of the community was ashamed of being native, I was native. Just like the Barbara Mandrell song, I was country before country, and that was cool. [laughter] I was an Indian before it was cool to be an Indian [chuckles]

IN: I like that. [laughter]

WD: So, growing up like that in the summer and in the winter, and it was just like that. That was our form of entertainment. But what was actually happening was we were being wired to our Rocky Cree culture. Because who we were, we were connected right from creation stories where the language becomes very- very crucial to understand the stories. Most people don’t understand the language which (ahh) they speak because they interpreted this way, they didn’t know. But it means native. In a sense it does, but realistically, ithinow [people]. When you study language, you study more theology than linguistics. And every word in the Cree language you can take apart and re-understand what it means. Like ithin means to put one concept into another and mix them together, which creates our creation story.

IN: Mm-hm.

WD: And my mom would share this story to us while she was making a bannock. How Wīsahkīcāhk was told, asked by the Creator, to make an ithinow, which, of course, Wīsahkīcāhk said, “Alright, I’ll make an ithinew.” What’s an ithinow? Okay, this is what you do [pause] you take earth [gesturing making a whole in a pile of flour with his hands].

IN: Ohh, okay.

WD: Take it out and leave a little whole in there. For the earth you took back. [ long pause] Your pour water into the (ahh) bowl that you made out of the earth. And you put back the earth in it. That’s the first ithin. Ithin means putting one and one together.

IN: Could you spell ithin for me?

WD: Ithin means [pause] I, T, H, I, N, ithin. It means when you put something, one and one. So that’s the creation story of (ahh) making a mud pie, literally. [chuckles]

IN: [laughter]

WD: Right?

IN: Yeah [laughter]

WD: And he (ahh) [chuckles] made the little human beings that way he was told. He put them on cardinal directions as we all know, we’ve been taught. And then (ahh) he was instructed to make a sacred fire in that place and how things have been taken out and made into little human beings. And the sacred fire was lit. And that sacred fire we call othaswina, laws that we have to follow. But it’s law that we love each other, it is law that we respect each other, it is law that we are obedient, it is law [pause] there’s lots of them [pause] sacred laws we lost that we [pause] follow. That’s the sacred fire, the eternal fire that burns today. That’s the third ithin. You have water, earth, fire. The fourth ithin [long pause] was after we were nicely baked. He gave us the gift of air [blows his breath out forcefully to represent a gust of air]. And we stood up.

IN: Wow.

WD: That’s ithin, ithinow, that’s what it means. A person made of four elements but [pause] that is structured to have… to follow the sacred laws. And then, from that beginning, we were given a miskanow. A life’s holistic journey. This takes days and days to tell how we are, its not [pause] all these short stories, some of them humorous, some of them tragic, some of them [pause] you know but they are all awakening stories. And [umm] as they- as the ithin was made. And that sacred flame still burns today. That sacred fire, its kind of smoldering sometimes some people say. But (ahh) with that ithin, we were directed to have a miskanow to follow. Holistic life path. Miskanow can simply mean [pause] You see that! [pointing at the window, looking at the road] That’s a road over there leading into the bush, that’s a miskanow. But we also have a (ahh) holistic journey of being physical, emotional, spiritual and mental. That holistic journey of going through life. The laws are set already, you know, we just have to. Miska means to find. MIS-KA.

IN: Miska.

WD: Yeah. Means to find. Miskanow, anow means choices. You can mithatnaw, a good journey [pause] by the choices we make. How we follow the rules around us. And then, of course, you have the negative journey to that, some of our relatives are in and (ahh) [pause] not being judgemental by the way. And macatnaw, your journey is not really that good. But the whole idea is to try and keep in balance. I’m sure you come to that time where you did some little bad things. We all have.

IN: [laughter] Let’s not go there.

WD: [laughter] Yeah. But we’re not going there [continued laughter]. But, (ahh) I think it’s the balance that counts. You know, to be able to realize [pause]. Yes, you make mistakes, get up! Keep going! You know, don’t try to portray yourself as somebody that’s never wrong, that never does wrong. Wait, we are all human beings, that’s the way it is! And, we were put on this mother earth to pause. We weren’t given a choice. We were gonna be born as an Irish man, Scottish, or Native! We were born [pause]. But it is very important for people to know their stories, our history. Because (ahh) having been there since I was a child, growing up around elders, knowledge keepers, storytellers, I naturally took that upon [pause] that no matter what my career was, to have that.

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: And in 1998, (ahh) when the (ahh) South Indian Lake was being flooded, two men were working for Hydro at the time: Bruce Tait and Bobby Moose.

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: They found a body eroding into the (ahh) into the water, into the water at Nagami Bay. At Nagami Bay [pause] and ingeniously, it’s amazing how they did it. They saved the (ahh) the remains. And that’s when the archeologist took it over. They did an amazing job too, an amazing job in (ahh) figuring out, you know, (ahh) what kayas ochi kikawinaw, that’s what we call her for lack of name, 350 years ago.

IN: 350?

WD: Yeah, when they found it. And (ahh) in1998, I think is the year they found it. And (ahh) I think it’s very important to give credit to the finder because [pause] in the long run it will give the community ownership, and this was found by two of their local people. And (ahh) Dr. Lee Sims worked on it and Kevin Prowley, too. Both archeologists from the museum [pause] and (ahh) it was amazing things that they documented. They documented [pause] and (ahh) [pause] they documented and while they were going along with this, I was pretty close to them [pause] we were pretty close. I would read through their manuscripts, eh? Through their manuscripts. It was amazing stuff that they found [pause] like kayas ochi kikawinaw had 2,000 pin cherry sheets on her necklace. Can you imagine, you know, making those by hand? Two thousand to make that beautiful necklace, but the other thing that they found in her was (ahh) red soap stone.

IN: Wow, nice.

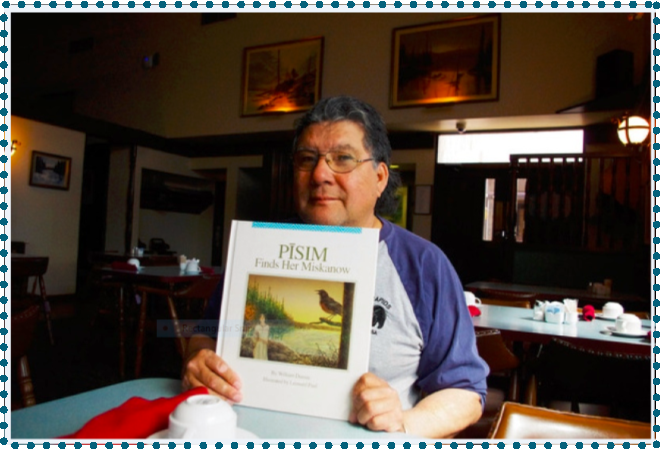

WD: Which proved to us- which proved to us that (ahh) that there was a very fast network of trading among the native people prior to the (ahh) Hudson Bay [Company] coming in. But the other thing about it was (ahh) they found a few European beads with her necklace. So, we figured this was post, just when the (ahh) the Europeans came, and trading began. So that was evidence. The manuscript itself was amazing, it was amazing [pause]. When I was teaching that time [pause] high school kids and I was thinking [pause] this will be like a punishment if I let them do this, go through this even amazing as it is. You know, because it’s like you have to go through a lot of information, and I thought. What is another way of doing it? And I thought, [da da da daa, gesturing with hands] and then I thought, okay! Write a children’s book. So little kids can be connected through their language, to their history, to their culture. To give them an identity of how their relatives lived long ago. And (ahh) having listened to stories since I was a kid [pause]. This book [pointing to a copy of Pĭsim Finds Her Miskanow] is made of little short stories that people have shared with me about being out on the land even when (ahh) Kāmisakāt has her baby. That was a story told to me by your great-great grandmother, Annie Moose.

IN: Okay. [With excitement]

WD: Yeah! She told me that story about her, you know, just going off on the side and having her baby moving along.

IN: So, in the story, that’s basically Annie giving birth and then…

WD: Yeah! Those are stories of how elders shared with me, how they, how they told stories like that. Even the robin is featured there [pointing at the illustration on the front of Pĭsim Finds Her Miskanow] that is the story my great grandma told me one evening. When the robin was singing. And she said, “Listen to it nikosis, what is it saying?” The old lady has gone nuts told the little boy eh? And when the robin sang, she sang with it. And she said, “Kinanāskomitin, opimāchihiwew kāpimacihiyin. I thank you, my Creator, for giving me life.” The robin sings that every morning, my girl. Every evening when the sun goes down. Never forgets to pray. We do, quite often.

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: So, the whole book is [pause] not only the work of William Dumas. It is the work of many people, research people, that we would sit around and [pause] work on it and how the people lived back then. So, children can explore how [pause] what their culture is. And by the way, this is the first of (ahh) five more books to come.

IN: Yeah? [With excitement]

WD: Yeah! We got five more books to come that will cover every season.

IN: Oh wow!

WD: Of how people lived.

IN: That would be great! Honestly, like my plan is to become a teacher. I could definitely see using this, like, it is so…

WD: There’s a teacher’s guide by the way.

IN: Yeah? [excitement] I was just kind of checking out the website. I haven’t looked at it, the app, in full but it does look very interesting because you have the knowledge pieces on it.

WD: My wife Margaret, and her team, they work on the teacher’s guide.

IN: Okay.

WD: We have these people working on certain parts, we have those people working on certain parts and then it comes altogether in book form.

IN: Okay.

WD: It’s not just the work of me alone. It’s a lot of people that have poured their hearts into it, to give that [pause] story line and the amazing thing about it is, none of them, [pause] most of them are non-native that are working on it from the University of Winnipeg.

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: And [chuckles] what we are teaching them at the same time is to be culturally competent, which is really [pause] give and take. How we work together. But that’s how the book was formed. It came out of the finding and when you look at (ahh) when you look at the (ahh) pictures, these are actually pictures of that area. When you go to Nagami, this is where her body was found.

IN: Yeah? I have been to Nagami once. When I first moved to South Indian, Kevin took us out there.

WD: So, this is (ahh) it. And sometimes what I do, what I do is, one day one of my nieces was looking at this thing. She said, “Uncle, this girl looks like me. [pointing to Pĭsim on the book cover]” I said it is you. [laughter]

IN: [laughter] That’s good.

WD: And a lot of the characters in here have names. They actually do exist. I use the names of people that are working along with me. I just use their names.

IN: Oh, yeah!

WD: It’s, it’s a…

IN: I have a question. You said this is at Nagami. Does my grandpa have a fish camp there too? Or is that a different one, Paul. Paul Spence.

WD: Yes! Yeah, he did have a fish camp in that area. Like the very next to them would be the Moose people, then Paul J. and them, Pukatawagan.

IN: Okay!

WD: So that’s [pause] actually your area.

IN: Yeah, I remembered when I went there, my cousin and they were telling us that it was my grandpa’s old fish camp. So, my mom was raised on those shores.

WD: Yeah, so the picture. And the other thing about this, these are pre-flint times. The pictures that are being used and over here like Crow’s point [pointing at a picture on the cover of his book] if you know, if kids study this, they will know where these places are. Some of them have…

IN: I saw the black wall, is that the one kinda close to the settlement [South Indian Lake]?

WD: Yes! That’s the wall.

IN: Okay, [excitement] when I was reading it [Pĭsim Finds Her Miskanow], I was like, okay, I’ve been there. Because Kevin took me there once, and he’s like you can climb to the top. And there are some people who even jump, I would never! But… [laughter]

WD: Yeah.

IN: But I remember- and I was like, I was thinking, because we went to Nagami. And you kinda see it on the way there, so that’s why I was…

WD: The story of (ahh) hole on the wall. And we’re working on a book about that, that’s where the little people live.

IN: I’ve heard of little people on Granville [lake] By- what’s the…

WD: Yes!

IN: Kee-Kee-Way, what is the island called? My dad took me there once. I can’t remember the name of the island you’re never supposed to point at. [laughter]

WD: Yes! [laughter]

IN: We make sure of it [not pointing] [laughter]

WD: I know the story of your dad camping there.

IN: [laughter] Ohh, okay! Because yes, I saw it and that looks exactly like what I’ve…

WD: Yes!

IN: The big rocks and moss and all that, so I found that super [pause], that was really cool.

WD: Yes.

IN: So what did your knowledge keepers, the ones that helped you? What did they reveal to you about the transfer of Indigenous knowledge? [long pause]

WD: Through the language, my girl, through the language. The language is very powerful. It’s a very powerful document and in the next few years as we develop linguists and anthologists. [pause]. The language will give us a lot of information about (ahh) who we are. And in (ahh) the culture alone. The (ahh) people in South Indian Lake, they still have the skills of 350 years. They know how to tan hides, they know how to smoke fish, they know how (ahh), you know, hunt on the land, although they use rifles. But…

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: They know how to do that. And the transfer of knowledge is still with us, we call it blood memory, those of us that study in that area. And that’s where that word, aniskotapiwin come from [pause] in our language. That’s the tie that binds, eh? The knowledge [pause] goes on and on and on. We, people, complain they destroyed our culture. No, they didn’t, we just have to find it again. And the finding…

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: Is the beautiful, the beautiful journey. And to the people being angry, go look for it! Go look for it! Okay, I’ll give you a little, a little (ahh) example. When I was a young man, I was a very angry, angry young man. And because I saw what had happened, the colonization, the destruction of economics [pause], you name it, you know, I was [deep breath], I was very angry. Watching our relatives lose their livelihood, eh? But at the same time, I was very interested in, nobody was interested in it, very few people I ran into, but a few people, a few of the elders would share information with me- would share information with me. One time I was complaining to (ahh) my mom. I said, “You know mom, we have no songs left. We have no songs left. Never heard a Rocky Cree song.” You guess, that’s not true, my son, the songs are storied on the land. [pause]. Look at the (ahh) poplar. It was kind of- I remember that it was kind of windy, a little bit. And you know how the poplars…leaves go [shooo shooo shoo shoo sho] [gesturing a shaking motion with his hands]. That’s your rattle, my son! There’s a song in there. Look at the waves. When the waves are moving…he said, that’s the way we sing, we don’t sing Sioux style or at the time, the word was Sioux. We don’t sing Sioux style words; we sing songs that come from the land. And (ahh) I remember one time (ahh) when I was working on Pĭsim Finds Her Miskanow. And then I was working on a story in (ahh) that’s gonna be coming out in print in (ahh) out of (ahh) out of (ahh) Eagle- Eagle Rapids. Just north of South Indian Lake, you have to go over beaver portage. [deep breath] They were berry picking there after a (ahh) fire. And they started to find along that area, there’s a beautiful hill. They started to find [pause] pottery, fragments of pottery. And because we were a big team, we went in there one summer and (ahh) documented all the areas where we found the (ahh) pottery. There were 51 sites. And you start to think, oh my god! How did people live around here? You know, they lived here, our ancestors were here, we never knew that!

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: We just thought they lived down the Churchill River. I said, “oh my god!” We started looking around right at Eagle Rapids. And we found that there was a weir that was there. We just thought for years [pause] it was part of the river system. We found that out and then we found some areas where they had moved rocks to make (ahh) bowls, where they would throw the fish in [pause] all of these things that we found, there was lot of information.

IN: That must have been fascinating.

WD: Yeah! It was just a fascinating journey! All these stories that I’ve done are just fascinating journeys of rediscovery. But going back to the songs. [pause] We have lost nothing! We just have to find them again, my girl.

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: And that’s gonna be the beauty, finding our stories again. And…

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: We still have stories, sacred stories that are [pause] probably hundreds and hundreds of years old. We have from creation story right to today. We have specific areas that we can say, yes! This is in. The kids learn about this time period. The thing is you have to understand the metaphors of storytelling because they did not have words. Like, after creation, time marches on and people became regressed in their behavior and the earth was clean. And the character here is Ayas and Ayas had (ahh) was instructed by the Creator to take the people that were still functioning well up on the hill, but it said everything is gonna be destroyed. And he was instructed to make five fires, in the cardinal directions. And dogs barking loud he (ahh) he did that in there (ahh) he was instructed to shoot his arrows into the air. At the time…

WD: Like the story of Ayas where he is shooting arrows into the air. And (ahh) they come down and everything starts burning. When you look at this story, we’re talking about meteor showers.

IN: Hmmm.

WD: That the (ahh) the metaphor for arrows, you know, fire falling from the sky. They talk about the (ahh) earth burning so fast that the lakes boiled and the big fish were, [William’s wife is talking to their son in the background] were done for and then the (ahh) other (ahh) part they talk about was the earth crack. And machipisiskiwak [bad animals] which is in reference to the dinosaurs, fell into those cracks and added fire and they said their blood [dinosaurs] started boiling out of the earth. Lava!

IN: Okay! That’s cool!

WD: So, that’s how the (ahh) the sacred parts to this story that we haven’t shared with the public yet. And that’s how knowledge was passed from the knowledge keepers, generation after generation, we kept those stories, they kept those stories alive. Passed onto us. Now the problem we’re having, why we think I refuse to retire [pause], the fluent language speakers are disappearing. They are aging and there’s no one behind them. Not many people are fluent.

IN: Even because the next generation, the ones don’t want to speak it.

WD: Yes! So, but for us, we think it is important for people to learn their language even when they’re 30 years old. And be able to pass on that information. Because once you pass on a story from the first language to a foreign language, it lost, it loses its flavour, of the sacred concept of that story. That’s why language is very crucial for me to keep it alive, because that’s the essence of our stories, to understand the language. Because it’s when you translate it into English it loses a lot of its essence.

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: So, it’s very important to keep picking up those stories.

WD: So (ahh) I think that’s where it stands today. Our knowledge keepers are very crucial. Because most of them are in their 60s, late 60s. I am going to be 70 years old next month, my girl.

IN: You don’t look like it.

WD: Huh?

IN: You don’t look like it! [laughter]

WD: [laughter] That’s what a lot of people say, so (ahh) that’s where they… it’s crucial right now, we are at a very crucial time. And (ahh) part of my work is documenting language and stories and knowledge, right now, so… I work with about ten knowledge keepers. But around me there are a lot of professionals that have made it the love,- their passion and love is there. They really got up in what we’re doing. So, I think it’s not lost, for me, I think right now it’s documenting it. So (ahh) in the future, students like you can come to that place and find that information you’re looking for.

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: That’s the beauty about what we do.

IN: So, I think you pretty much answered the second question on why culture is so important and how it influences Indigenous societies today. But I wanted to go onto a third question, how can we get our children to be more interested in our traditions, such as the transfer of Indigenous knowledge? —Now, honestly, I think this is part of it. [pointing at William’s book, Pĭsim Finds Her Miskanow]

WD: Uh-hm.

IN: Having something they can look at and be like, Okay! Having that connection, but I think…I’d like to hear more from you, your perspective.

WD: I think, my girl at this time, I think the responsibility is on the parents. Where parents reconnect their children to their language and their culture. The school cannot do it alone. You know the school cannot do it their own, although it’s a big resource. I think for people who want to connect their children to the old stories, it has to start in the home. And once it’s in the home, you know children have books like this laying around [picked up a Pĭsim Finds Her Miskanow] And I hope there will be more, more authors that-I hoping. [pause] That was the whole idea, it is to encourage people like yourself to write stories about what you heard. From your grandparents, that you remember. Because that what this book is about and that’s the crucial part. It’s [pause] where do we start? We start by doing. Not talking.

IN: I like that. Start by doing.

WD: And yeah. If we do that and give tools for parents to use to connect their children. It’s amazing! I got a call the other day from a little Cree girl that’s going to school around the Selkirk area. “Mr. Dumas, can you come to our school? We are reading your story and we love it and we want to meet you” [said the little Cree girl]. So, it happens constantly eh?

IN: Yeah!

WD: It happens constantly because [pause] in today’s time, technology has become our [pause] our storyteller eh? Kids learn to be like Bart Simpson. That’s not a really good role model. [laughing]

IN: [laughing] No.

WD: But you see kids, you know they think that’s normal? It isn’t! I’ve seen kids being raised by the cookie monster.

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: I’ve seen kids being raised by [pause] by [ahh] SpongeBob and Bart Simpson. So, the media has [ahh] taken over in the guidance of our children. So how do we get them back to us? [pause] Like, do you have children?

IN: Yes, I have a little boy.

WD: How old is he?

IN: He is two.

WD: You’ll be surprised, by the time he’s five and six years old, he’ll be more tech savvy than you! [laughing]

IN: [laughing] He only gets his iPad when we travel. So, he doesn’t get it at home.

WD: That’s good.

IN: But when we are traveling, the kid knows how to do it all. I’m like, I don’t even get it! I’m like, “How did you learn to do that?” [laughing]

WD: That’s the amazing thing. And I think [ahh] not to get him away from technology because technology is with us now.

IN: Yeah.

WD: I’m glad kids are learning how to do it, but we have to find ways to connect them to their culture.

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: Through their language and [pause] So, we got to get into the-the APP world, you know? For kids because we are also creating apps for language, you know. We are creating word lists for language; we are working on those areas.

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: And [ahh] [pause] It’s amazing! In order to [ahh] reconnect [pause] children to their past, the parents need to have a buy in. And if they can have a buy in, they can take time and say,

“Come here my boy, I want to read this story for you”.

IN: Uh-hm.

WD: And show them. So yeah!

IN: That’s what we do [my son and I]. We read our stories.

WD: We often think it’s in today’s society. We and our children were given to the schools as early as full time in the late 50’s. So, now we have to take our children back. We have to become parents and that’s a very crucial part where you hear a lot of native people saying “I didn’t learn to be a parent”. [pause] I didn’t learn to be a parent, but it’s never too late, you know?

IN: Yeah.

WD: I’m a parent. I can’t tell anyone this is how you raise kids because I come from the same block. I made mistakes; I made some good choices for my kids… [pause] Today, they are okay. They’re okay. Struggling with life but, you know, my grandkids, they love that book. Because that’s grandpa, you know? So, that’s the way we reconnect with the kids…children. We can’t expect the schools to do it all. They are beautiful parents, the teachers. But the parents have to reconnect their children to the past.

IN: Yeah, it has to be our first parents.

WD: Yes, when you look at [ahh] [pause] my generation, many of us were not connected to who we were. We were ashamed of who we were. Now we have to find that pride again. I once asked a native teacher, “What’s the hardest part about teaching Cree?” And she said, “It’s like pulling teeth.” Kids come to school ashamed of who they are, of what their language is. So, we have to figure a way of bringing that pride back to them. But if children are coming to school being ashamed, are they learning it at home? I wonder. Some of them? I’m just wondering, I’m not pointing fingers. Just a question. But at the same time, the other side of the coin, there are a lot of non-native people out there. And I think it’s very crucial for us to show them who we really are. Because for some of them, what do they really see of native people? Or the street people.

IN: Yeah, the ones they see out everyday. Not the ones in the libraries and…

WD: Yeah! Yeah! So, you got to try to reconnect the non-native kids to stuff like that so they can have a better perspective of who we [Native people] are, you know? I think we need to move forward.

IN: Oh, yes! I definitely plan on implementing that when I’m a student or a teacher.

WD: Right on. That’s good to hear.

IN: Uh-hm. My major right now is Aboriginal and Northern Studies. It’s been so rewarding. I didn’t grow up with it, I grew up in the States away from it. I came once a summer and hung around my grandparents.

WD: It’s a wonderful journey of rediscovery, isn’t it?

IN: It is! Everything is so beautiful.

WD: Could you imagine if as a teacher, you are helping kids rediscover what you discovered?

IN: Uh-hmm.

WD: That’s amazing. It’s beautiful.

IN: It’s been some of the best years of my life. Like, learning about everything. [long pause] I’m so passionate about it now. [laughing]

WD: Me too! It’s been my love and passion all my life. Like I said earlier, the beginning of the interview. “I was native before it was cool to be native”.

IN: [laughing] I like that a lot! That’s awesome. [laughing]

WD: Do you have any supplementary questions?

IN: Umm? I was going to ask what else people need to heal but you pretty much covered that. That we need to connect back to the culture in order to heal.

WD: Yes!

WD: And [ahh] Although right now, for a lot of people healing is insurmountable. But at the same time, when people begin to take that journey, they are going to find that it’s a beautiful journey of accepting who they are.

IN: Uh-hmm.

WD: You know, accepting that their language is beautiful and not… It’s a beautiful language that has rhythm, that has…

IN: I just wish I could…Because when I hear my mom and her sisters around, everyone is just laughing…

WD: It’s like a song, isn’t it?

IN: Yeah!

WD: It’s like a song, that what I think.

IN: Just wish I could understand.

WD: Because years ago, I was asked at a symposium, “Why do kids need to learn the language?” Well, there’s lots of reasons why. Rediscovery, history, even genealogy. Stuff like that. But look at this…When you speak your language, there’s a rhythm to language. That’s how we walk, that’s pride. And I think, sometimes I look at kids trying to portray other people that they are not. They walk like that…but when you see them walk away after, they are back to their rhythm. But the thing is, most children right now are caught in language transition, eh? [pause] So, that’s a very deep sociological concept that we need to take a look at. We need to [ahh] [pause] I think we need to find innovative ways of doing this work, the healing. Healing is very crucial. Without healing, we are a lost people.

IN: Uh-hmm.

WD: We lose our language, we become lost in our miskanow [journey]. We lose our stories, we become lost. So, it is very crucial that we always identify what these stories are about…to learn like me. From the time…I’m not saying I am better than anybody…I was very blessed and lucky to sit around and listen to the stories. Even to this day, I am a story hunter.

IN: Uh-huh.

WD: Across Canada

IN: That’s awesome.

WD: But I work mostly with the Cree people, eh? The Cree speaking people and I find there are a lot of similarities in the language…the stories and in the sacred knowledge that we carry. Just yesterday alone, [pause] I was standing outside with some knowledge keepers, and they said “Hey! We’re living in a time of prophecy, we’re the fifth generation. Our children, our the sixth, our grandchildren are the seventh. They are going to be a lot stronger than we are.” And one of them said, “Yes! They thought they buried us, they didn’t realize we were seeds.

IN: That’s great.

WD: And that what you have to look at yourself too Alicia. You are a seed of what is yet to come.

IN: Uh-hmm.

WD: I think there will be struggles, but I think for people that get [pause] blessed enough to say this is my love and passion. My language and my culture, my stories, my history. I think things will start to get better.

IN: Yeah.

WD: Start to get better because we are walking towards that prophecy of the seventh generation, eh? And then again it will start a new cycle. [pause] Because when you look at who we are, damnit my girl, we were amazing scientists. When the world starts to find… look [pause] we are the only people that figured out there are six seasons to a year cycle. Six seasons [pause] and [ahh] not four, six. And those six seasons are divided into [pause] two moons to a season- two moons to a season. And each moon has 28 days, and like the elders use to say, Mina apisis. My god, fraction! Mina apisis in a little bit. Look at it this way, 13 moons and one of them sits on top all the time and that’s the one that moves things forward. And another one comes up there and moves it forward. How the hell did they figure that out?

IN: [laughing]

WD: [laughing] Every moon my girl, has 28 days. 28 days times 13 is 364 days. Mina Apisis, people say there are four dark nights. These… but our people said there are two dark nights that end. And the mina apisis is here. Kicks into a new moon cycle, two dark nights [pause] fractionally they figured it out, it come to 365 days per cycle. [long pause] So, can you imagine what it’s going to be like to connect children to that information?

IN: Uh-hmm.

WD: How…

IN: It will enlighten them.

WD: Yes! A lot of Cree people say… when I talk about these things, they just go “Oh my god!”

IN: Uh-hmm.

WD: You know the knowledge keepers I work with… because this has been my journey. They are just dumbfounded… just amazed like “I didn’t know that!”

IN: [laughing]

WD: And now you know, you know?! [laughing] Now you know! So, there are a lot of… in the healing journey that [pause] that we’re going to be in. I think we are going to work towards being human beings again. Not perfect, human beings. Where we are going to be both good and bad. But try to stay in balance to walk that beautiful journey, eh? And that’s where our songs come from. It’s that time my mom told me about our songs that are on the land. I remember… going back I was… Sitting ice fishing, eh? And at Chapman Lake, and a teacher was teaching, and she was very curious about me. Every chance she got she would come chat with me. She came and sat on my skidoo and she said, “William, where do the songs come from?” I said it’s easy, and I started singing a song. And then she looked at me when I was done, “Where did you get that song from?” Look at the contours of the land [long pause] that’s where the song is.

IN: Uh-hmm.

WD: Not coming from the south, it’s right here. That’s the beauty of the healing journey of rediscovery. You know, finding things out for yourself. Having that quiet time. A lot of people think I’m a public person, I’m not! I’m basically a recluse, I like being alone. I like driving [pause] for miles and miles and sometimes people travel with me with a tape recorder… [laughing]

IN: [laughing]

WD: Really! Honest! [laughing]

IN: Yeah! That’s awesome! [laughing]

WD: There’s a lot of people that have- that do that eh? You know they are story collectors and so they say, “William, when is your next trip? Can I go with you?”

IN: [laughing]

WD: I said sure, if you pay your way. I’m not paying for your food… [laughing]

IN: [laughing] I’ll give you stories, that’s it… [laughing]

WD: Yeah! But I think it’s very important, you know, we share what we have because some of the people who do that are non-native, you know? [chuckles] There are story collectors everywhere. So, I give them those stories [pause] hoping that [pause] down the road they pass them on to my children.

IN: Uh-hmm.

WD: And when they are ready to listen… So that’s how it goes, the healing journey we are in, it’s beautiful! It’s beautiful. We have a lot of disease to look after. Most of our communities operate on gossip, eh? Technically, in Cree gossip is lying about someone.

IN: Yeah? Wow, I didn’t know that.

WD: Yeah, that’s…they are made up stories. So, we have a disease that [pause] we need to address some diseases. We cannot be pointing at those people that took away our culture and our language… that… [pointing outside] Get it back!

IN: Uh-hmm.

WD: So that’s all you have to do instead of complaint.

IN: Uh-hmm. Break the cycle.

WD: Yep! Break the cycle of blame. [long pause] And that’s where the beauty is, to be able to come to peace with yourself and I think that is so important to give that to the kids. So, they are at peace with who they are. So, they will say, “Alright, I want to be a pilot, I want to be a taxi driver, I want to be a doctor, I want to be a carpenter, I want to be a lawyer [pause] I want to be a teacher, pass this information on to the little ones that need it. And there’s a lot of beautiful teachers out there right now, that are doing this work, quietly, you know? Just… moving along. And, [ahh] [pause] I don’t think its only teachers though. I think there’s people like [long pause] you, people like [pause] others. I can visualize them. They are not teachers, but every chance they get they will talk about what they’ve learned. Pass it along. And that, I think the journey together, nichiwakan and that miskanow, my partner. So, that’s [ahh] I’m excited about it. [pause] I’m at peace about it because [pause] I don’t have many years left in this [pause] element. But I hope to god I have influenced…

IN: Yes.

WD: Enough people that they continue the journey.

IN: Honestly, when we came up with this… when we were presented with this, you came to my mind first off. And it wasn’t just because we both are from South Indian but it’s because you are very influential.

WD: Yeah?

IN: You are! And it’s been a pleasure. I thank you very much. Unless you have any questions for me, I will conclude the interview. Umm…

WD: Uh no. If you need anymore information, my door is always going to be open.

IN: Okay, perfect!

WD: Just call me.

IN: I have your number now, so I will. [laughing] Alright, that’s concluding my interview with William Dumas, thank you!

Author Note: This transcript was prepared for ANS 3400, Philosophy and Culture of the First Nations of Northern Manitoba taught by Dr. Jennie Wastesicoot.

About the Author: Alicia Stensgard is just finishing her 3rd year of the Bachelor of Arts Program from University College of the North. Next year she will attend Brandon University to start the Bachelor of Education’s After-Degree program. As an Indigenous woman, Alicia is very passionate in her studies of Aboriginal and Northern Studies in which she majors. She minors in Social Sciences and has had great academic success at UCN. The professors, staff and students have made her experience at UCN a memorable one. This interview with local author William Dumas is significant to the rediscovery of the Cree culture in Northern Manitoba and other Indigenous groups alike. The transmission of Indigenous knowledge is a topic that is very influential to Alicia through her studies at University College of the North.

Instructor’s Remarks: Finding an aboriginal traditional story teller is not easy. Alicia Stensgard was attending the course of “Philosophy and Culture of the First Nations of Northern Manitoba” (ANS 3400) with me in the fall of 2019. It was fortunate that she was able to interview an Elder from her own home community, O-Pipon Na Piwin Cree Nation (South Indian Lake). Focusing on the theme of “Telling Our Stories,” Alicia was able to capture and document the Elder’s concerns of storytelling and his way of sharing stories. Alicia’s transcription is well written, and it carefully narrate making it very interesting and fascinating to read. The interview also illustrates why it is important to share stories – Dr. Jennie Wastesicoot.